CHAPTER 7: FORCED DISPLACEMENT

We are No One: How Three Years of Atrocities Led to the Ethnic Cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenians

Chapter 7. FORCED DISPLACEMENT

CONTENTS

I. Introduction

II. International Legal Framework for Forced Displacement

III. Key Findings

1. Physical Attacks

2. Intimidation

3. Attacks on Sources of Livelihood

4. Lethal Restrictions on Freedom of Movement

5. Disruption of Energy Infrastructure

6. Endangering Food Security

IV. Conclusion

I. INTRODUCTION

From the beginning of the 2020 war and beyond its end, Azerbaijan deployed a series of mutually reinforcing measures that made life in Nagorno-Karabakh impossible for its 120,000 inhabitants. These three years of violent and increasingly untenable conditions created the underlying conditions for the liquidation of nearly all the region’s ethnic Armenian residents in September 2023.

However, even before this most recent mass dispossession from Nagorno-Karabakh, several waves of forced displacement had already taken place. Thousands of ethnic Armenians had fled the areas of Nagorno-Karabakh that were overtaken by Azerbaijani forces during the 44-Day War or were forced to leave under the terms of the November 9, 2020 ceasefire agreement. Subsequently, Azerbaijani forces continued to intimidate residents of border communities following the war, causing further forced displacement within and out of Nagorno-Karabakh in the years leading up to Azerbaijan's decisive takeover of the region in September 2023.

The University Network for Human Rights (UNHR or University Network) has classified the primary mechanisms of forced displacement employed by Azerbaijani state forces into six categories: physical attacks, intimidation, attacks on sources of livelihood, lethal restrictions on freedom of movement, disruption of energy infrastructure, and endangerment of food security. The incrementality of forced displacement, and the six primary modes by which it was carried out since the beginning of the 2020 war, are described in greater detail below, using evidence from UNHR’s fact-finding and interviews as well as secondary source research.

II. International Legal Framework for Forced Displacement

Forced displacement is the coerced removal or relocation of a person or persons from their home or region.1 Displaced people can be refugees: people “who [are] unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.”2 Or they can be internally displaced persons: people “who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence…to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized State border.”3

Humanitarian law, human rights law, and customary international law provide safeguards against forced displacement. Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention prohibits “[i]ndividual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory to the territory of the Occupying Power or to that of any other country, occupied or not.”4 Several human rights treaties, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,5 the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,6 the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination,7 and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women8 impart obligations on States regarding freedom of movement that protect against the involuntary displacement of people. The Rome Statute provides further protections, stating that forced displacement or transfers can be considered crimes against humanity (Article 7.2) or war crimes (Article 8.2).10 The International Criminal Court has clarified that displacement does not require that people be physically forced from a location. Threat of force alone based on “fear of violence, duress, detention, psychological oppression or abuse of power against such person or persons or another person” is sufficient to be considered forced displacement for crimes against humanity purposes.11

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement provide further guidance. Though the Principles are not binding, they “restate and compile human rights and humanitarian law relevant to internally displaced persons,” serving as the blueprints on the matter.12 The Principles state, “Every human being shall have the right to be protected against being arbitrarily displaced from his or her home or place of habitual residence,”13 and they place a particular importance on protecting “indigenous peoples, minorities, peasants, pastoralists and other groups with a special dependency on and attachment to their lands.”14

III. Key Findings

1. Physical Attacks

Many of those who fled Nagorno-Karabakh and/or border areas following the 2020 war's end did not do so as refugees of since-ended violence; rather, they were escaping due to ongoing and armed aggression against their communities in violation of the terms of the ceasefire agreement.

One of the principal forms of violence that drove many from their homes was Azerbaijan’s use of intense and persistent shelling. For instance, in Khramort, a village on the eastern border of Nagorno-Karabakh close to the frontline, residents claimed that the shelling that occurred at the onset of the war still continued when our team interviewed them in March 2022, just one day after they fled to Stepanakert. Susana, an epidemiologist who lived in the village with her daughter and grandchildren, had already been displaced earlier in the war from Hadrut, the location of some of the most brutal killings of civilians during the 2020 war (see Chapter 3. Unlawful Killings). In Khramort in 2022, she explained how relentless shelling had impeded simple day-to-day activities and caused many to flee. “There is no way to continue living in Artsakh. They are violating human rights in every possible way from every possible side,” she said.15

Melik,16 a resident in the Armenian border village of Sotk, described the near constant shelling during Azerbaijan's attacks of September 13 and 14, 2022. “Every minute, every hour you can hear their aggression.”17 Samvel,18 another resident, told UNHR, “There were hundreds of bombs and you couldn’t tell if they were going to hit you or hit next to you. You just try to save who you can.”19 David,20 a schoolteacher, experienced the shock of nearly walking into the path of an explosive. At home with his wife, parents, and small children, he said they were already sleeping “when we woke up to a very loud noise. My father and I ran outside. A bomb fell right in front of us when we stepped outside. The wave from the explosion broke our windows. We ran inside to get our children to the basement and prayed that we wouldn’t be shot.”21

David mourned the impact the shellings have had on his children. “The worst is for the kids. My older son is three years old. [During the attack] he was just holding tight on me. He wouldn’t cry or make noise because he kind of understood what was happening. This is a curse on them.”22 On the trauma of the shellings, Artur,23 a fellow resident of Sotk added, “If you haven’t seen it with your own eyes, it is hard to tell you. You have to see it, to feel it. We were being shelled from three different sides. It was chaos, the kids were crying. It felt like something out of a movie. We had to grab our children. They were clinging to our legs.”24

The residents of Sotk were convinced that their homes were a target, and that the goal of the shelling was to make them want to leave. Melik reflected,

"If it was only one or two houses, it may not have been deliberate, but over 90 percent of houses were damaged. Therefore, it was deliberate. Two days in a row, they were shelling houses. They just want everyone to leave the village. If they wanted to target military posts they would have targeted those directly, but we had so many missile strikes in the village that it was clear that they were aiming here."25

Intentional or not, the consequences have been clear. Samvel said, “My friends and a few other people I know have stayed, but most left. Around 95 percent. Many have not returned even after renovations. Everyone is moving to Yerevan.”26

The activities of the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC) demonstrate an awareness that civilians in Armenian border communities are in danger of continued Azerbaijani attacks. Most telling is the ICRC's program to build “passive protective measures” in a number of border areas. These measures are physical structures, such as walls, that can offer refuge in case of artillery fire or shelling on residential areas. An ICRC spokesperson elaborated in an interview with UNHR researchers,

"We are also building safe rooms in basements in border schools so, in case of shooting or shelling, students can take refuge for a couple hours. . . . Protection ensures that there are protected walls in case of stray bullets. The walls are usually built in front of the schools. Walls help ensure that in the daily routine, there are passive measures."27

The ICRC had built 130 saferooms when UNHR interviewed them in March 2022, mostly in the Tavush region of Armenia, where “shootings are pretty close to the border.”28

The repeated shelling by Azerbaijani forces have wrought lasting psychological and physical impacts on vulnerable families in Jermuk. Communities were shocked upon witnessing attacks on Armenian land when the shelling commenced. One mother noted, “I never imagined such a thing like this could happen in Armenia or Jermuk. . . . Even with the border 12 kilometers away, we couldn’t imagine we would ever be under attack.”29

These Armenian communities faced an increased military presence, harrowing sounds of shelling, and the sight of their town filled with shrapnel and shell casing. “Seeing the damage from the shelling on my way home, I just turned around to go back to the village in tears,” one interviewee said. “Seeing the great green forest covered in smoke and the craters from the shells made me believe that I would not come back to Jermuk.”30 Another mother noted, “We live in fear and hope none of the shelling hits.”31

Even after bombs stopped falling, the psychological harm inflicted by the trauma of the shellings impedes civilians from reconstructing a sense of normalcy. In the village of Sotk, school teacher David noted, “I would say the biggest challenge among our students is the fear. For one to two months, education was mostly online, and it was challenging. The sense of fear is still here. Even though we have returned to our normal education, there is still fear.”32

The September 2022 attacks also led to a noticeable exodus from border villages in the Vardenis Municipality of Armenia. The village head of Kut, one area University Network visited in March 2023, described how the attacks pushed residents out of the village: “Right now, there are 33 families in Kut, 100-plus people. Before the September 2022 attacks, there were 52 families living in Kut. [During the attacks] ten houses were damaged, the municipal building was damaged, and the community health center.” According to the village head, Azerbaijani forces attacked Kut on September 13 and14 from positions they had taken subsequent to the transfer of Kalbajar (Karvachar in Armenian) to Azerbaijan under the terms of the November 9, 2020 ceasefire agreement.33 This is a crucial observation because it illustrates the incremental territorial encroachment mentioned above: Azerbaijani armed forces moved beyond the positions they held at the conclusion of the 44-Day War in stages, ultimately arriving at a position to carry out the September 2022 attack on Kut and other communities in Armenia.

2. Intimidation

Azerbaijan’s intimidation of border communities, which coerced many to leave their homes, took a number of forms in the wartime and postwar periods. These included threats of further military action and physical attacks, Azerbaijani government surveillance, and arbitrary detention of Armenian civilians or troops inside Nagorno-Karabakh and undisputed sovereign Armenian territory, as well as at border crossings.

A man named Vahram, who at the time of his interview with UNHR in March 2023 was stuck in Goris along with his family, had a threatening encounter with Azerbaijani forces while driving back to Nagorno-Karabakh with his family at the end of December, after the 44-Day War had ended. When they passed by the Azerbaijani military security in Shushi (Shusha in Azeri), the soldiers shouted,

“We will kill you.”

Vahram described how his children saw and heard the threat, and how he tried to convince the children that it was a joke and that they should not give it any attention. Vahram also described how “the Azeris made a sign to kill the kids,” by dragging a finger across their throats, mimicking it being cut, as he and the children drove past.34

Evidence suggests these threats were not made by individuals acting of their own accord, but rather in adherence to an underlying policy. Several people from different areas in Nagorno-Karabakh with whom we spoke discussed the use of loudspeakers to broadcast harassing messages pressuring residents to evacuate the area. Susana’s daughter Tamara remembered an especially intimidating and effective announcement from March 2022:

"Leave the land. You are currently in Azerbaijani territory. This is not your land, we do not take responsibility for you, we do not guarantee your safety. If you love your children, abandon this territory."35

The Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh documente

d what appears to be the same recording of threats by Azerbaijani forces over loudspeakers beginning February 24, 2022:

You are in the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Any action carried out here is regulated by the laws of Azerbaijan. Everything you do without official permission is illegal. The agricultural work you are currently carrying out is illegal. Do not prepare for war, do not try to create a border in our territory. If you want to stay and live here, obey the laws of Azerbaijan. Taking into account your safety, we demand to stop the work and leave the area immediately, otherwise FORCE WILL BE APPLIED on you, the responsibility for the losses will fall on you. Do not endanger the lives of your family members. Leave the area, leave the area.36

Azerbaijani media reported that Azerbaijani forces used the same loudspeakers to play the azan, the call for Muslim prayer, throughout Khramort village, “in commemoration of the Khojaly massacre.”37

The use of loudspeakers to threaten and intimidate residents was also documented in other villages in Nagorno-Karabakh, including Karmir Shuka and Taghavard in the Martuni region, and Khnapat, Nakhichanik, and Parukh in the Askeran region.38 These messages caused residents immense psychological harm and prevented them from engaging in their normal daily activities. The Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh described the lasting effect these threats have on those who remain: “Parents do not send their children to kindergarten or school due to security concerns, which violates the right of children in the community to receive a proper education. Under these threats, agricultural work is not carried out, which is the main means of livelihood of the rural population.”39

Drones were another source of intimidation in border communities. In Kut, a village in the Syunik province of Armenia, one resident described observing how close Azerbaijan's drones hovered during the September 2022 attacks: “After the war, we always saw drones. Not before the ceasefire. . . . On the 13th, the drones were lower in the sky to provide visibility for them.”40 Residents of Sotk were also personally familiar with Azerbaijan's use of what they described as investigative drones launched from their positions within eyesight of the building block where UNHR was conducting interviews.

Abductions by Azerbaijani forces in border areas became increasingly more frequent throughout the postwar period, not only in Nagorno-Karabakh, but in Armenia as well. On some occasions, Armenians unknowingly crossed into territory that had fallen under Azerbaijani control. In others, Azerbaijani forces crossed into territory under Armenian control and attacked, threatened or abducted Armenian civilians. (See Chapter 1. Arbitrary Detention.) Below are examples of just some of these abductions, which have been exhaustively documented primarily by the Human Rights Defenders of Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia.

- On November 23, 2021, in the Martuni region of Nagorno-Karabakh, local authorities reported that a 21-year-old Armenian got lost and accidentally ended up in Azerbaijani-controlled territory. His release three days later seemed to result from negotiations conducted with Russian forces.41

- On July 19, 2021, in the village of Tegh in the Syunik region of Armenia, a man crossed the invisible demarcation line into Azerbaijan’s occupied territory while plowing with his harvester. After the man returned to his own land, Azerbaijani soldiers trespassed into Armenian territory and detained the man and his harvester. The commander of the Russian forces, the commander of the army corps of the Armed Forces of Armenia, and representatives of Azerbaijan engaged in five hours of negotiations to have the man and his equipment returned.42

- On July 22, 2021, a resident of the Aygestan village of the Askeran district lost his way in the area of the Khramort municipality and crossed into an area controlled by Azerbaijan. After hours of mediation by the Russian forces, Azerbaijani officials eventually returned the man.43

- Around July 26, 2021, the staff of the Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh received an alert regarding the arbitrary detention of Artak, a 32-year-old resident of Machkalashen community in the Martuni Region of Nagorno-Karabakh. The cattleman was captured by Azerbaijani soldiers after inadvertently crossing into occupied territory while searching for a lost cow. The municipal authorities appealed to the Russian forces in an effort to have the man returned safely. Following significant mediation, Azerbaijan eventually released the man.44

A common theme in these abductions is the targeting of agricultural work and animal husbandry, which in turn immediately harms sources of livelihood and food security. University Network researchers spoke with those directly targeted and affected by such attacks in Armenian border communities and with ethnic Armenians recently forcibly displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh. We share some of those accounts below.

3. Attacks on Sources of Livelihood

Attacks on sources of livelihood were a common theme in accounts of intimidation against residents of border communities in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. University Network researchers documented reports of Azerbaijani attacks on farmers and cattle raisers, including detention, death threats, opening fire on workers, and stealing cattle. These attacks were described by residents of border villages not far from Stepanakert in Nagorno-Karabakh, as well as in Kut and Sotq in the Vardenis region of Armenia, and Nerkin Khndzoresq in the Syunik region of Armenia. The more permanent fact-finding efforts on the ground (in particular, documentation by the Human Rights Defenders of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh) have registered countless more incidents of attacks on agricultural workers and assets. As a result of the frequency and widespread nature of attacks on agricultural work, many have simply stopped working the land, or drastically reduced the area of land that they cultivate or in which they allow their animals to graze.

The inability to provide for themselves and their families as a consequence of Azerbaijan's armed attacks, seizure of farmland and pastures, intimidation, and living under siege, has undoubtedly been a significant contributor to the suffering of the inhabitants of Nagorno-Karabakh since the end of the 44-Day War.

The blockade of the Lachin Corridor has been a significant cause of disruption in sources of livelihood. According to analysis conducted by the Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh, in the first six months of the blockade, Nagorno-Karabakh saw a cessation of over 85 percent of production and 100 percent of exports.45 As a result, the construction of critical infrastructure, including roads, water pipelines, irrigation systems, apartment buildings , and industrial facilities, came to a complete halt.46 As of June 12, 2023, an estimated 11,000 people – over 60 percent of Nagorno-Karabakh's private sector workforce – had lost their jobs or other sources of income.47

Even before the blockade, the Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh has documented detailed accounts of the use of high caliber weapons, including grenade launchers and firearms, on agricultural lands and equipment and near administrative and residential areas in Khramort and other border villages, prompting the evacuation of women and children as well as the cessation of all agricultural activity. Over a period of five days March 2022, shelling from Azerbaijan pushed Armenian residents in seven different communities from two of the easternmost regions of Nagorno-Karabakh to cease agricultural work and thus sacrifice their only source of livelihood, as well as to abandon their homes.48 In a report published in March 2022, the Human Rights Defender stated that “Russian peacekeepers are unable to provide security guarantees for civilians engaged in agricultural work.”49

A year later, when University Network researchers returned to Armenia to conduct additional fact finding, we found that Azerbaijani forces had attacked sovereign Armenia as well, particularly in border villages of the Vardenis and Syunik regions, using the same tactics: shelling of administrative and civilian structures, firing on agricultural and grazing lands, as well as killing or theft of livestock.

Agriculture and animal husbandry are among the primary sources of livelihood in Armenia. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization, agriculture is the main source of economic activity in rural areas in Armenia, and livestock breeding represents almost 40 percent of Armenia's gross agricultural product.50 The importance of agricultural work and animal husbandry for communities like Kut cannot be overstated. The constant threat of attack on livestock and cattlemen has put an enormous strain on families living there.

Hayk is a 31-year-old father of five small children – two boys and three girls. At the time of his interview with University Network, one of the children was just one month old. He narrated the events leading to the day that all of his cattle were stolen by Azerbaijani forces:

"On June 5th, 2021 I took the cattle down to the stream to drink. When they heard the shots one group of the cows ran away. One of the shots hit my horse's leg. I hid in the trees. I saw three Azerbaijani soldiers come down from the heights and push the remaining cows across the stream over to their side."51

In a separate conversation with University Network, Kut’s village head provided additional context: “When this was happening, other villagers heard the shots being fired. They tried to reach Hayk but the Armenian soldiers stationed nearby wouldn't let them through. They explained that it would be too dangerous and could cause an escalation.”52

Hayk concluded, “I thought there was some way I could get the animals and bring them back. But after they were taken across, I realized it would be impossible.”53 The impact of Azerbaijan's attacks on cattle-raising in Kut began before Hayk lost his herd. The village head explained,

"There are pastures that were taken on May 12, 2021. The situation in the pastures is awful. Most are now under Azerbaijani control, and the parts that are under their ‘eye’ are dangerous."54

Beyond targeted abductions, shooting, and theft, the Azerbaijani military has reportedly set fires to the pastures close to the border, aiming to deprive the Armenian citizens of border areas from their means of subsistence and threaten their security. According to the Armenian Human Rights Defender’s report, on August 29, 2021, in a number of villages in the Gegharqunik region (where Kut is located), “270 hectares of pastures and 150 hectares of grasslands have been burnt in 4 villages.”55 On September 4, 2021, also in Gegharqunik, on the road from Norabak to Azat, “about 40 hectares of pastures have been burned down, [including] the grass from which the villagers used as animal feed,"56 the Human Rights Defender reported.

Zoya, a mother of two boys, described to UNHR researchers how being deprived of access to farmland and pastures has impacted families in Kornidzor, a village in the Goris Municipality of Armenia within eyesight of Azerbaijani military positions:

“In the village in general, our lives have changed. All of the fields have been taken, so there are no jobs with agriculture and crops. Because there are no jobs, people leave the village. They used to take care of livestock and the fields.”57

In the communities that depend on livestock, farming and pastoral land for subsistence, alternative sources of income and prospects for economic growth in general are scarce, not least because of the proximity of these villages to Azerbaijani military positions. Zoya described how life in the villages on the Armenia-Azerbaijan border is characterized by constant fear and uncertainty about the future:

“We go to bed worried about the next day. We are surrounded by Azerbaijan on almost all sides. There are many military checkpoints; from here we can see the Azerbaijani trenches and checkpoints.”58

Agriculture and livestock have not been the only sources of livelihood targeted by Azerbaijani forces. Tourism in areas dependent on it too has been impacted by Azerbaijani violence. When UNHR researchers visited Jermuk in March 2022, we sidestepped the remnants of a cluster munition peeking out of the snow as our host, the owner of a popular ski-lodge and renowned cable-car, pointed out deep gashes in the trees and missing chunks from the side of the wall of the ski-rental building and cafe.When asked by UNHR researchers if he had ever imagined something like this happening to the lodge, he had to pause and pull himself together before responding, “No, never.” As we observed the stalled cable cars in the gorge above us, he recalled, “on the afternoon of September 12th [the day before Azerbaijan attacked], there were 240 people on those cable cars. Even though they completed essential repairs to the cable car after two months, he estimated that tourism to the lodge had dropped around 80 percent since the attacks.59

4. Lethal Restrictions on Freedom of Movement

Azerbaijan's obstruction of freedom of movement along the Lachin Corridor has gradually increased since the end of the 44-Day War. Based on information gathered by the University Network through conversations with individuals and organizations familiar with the process of transiting the Lachin corridor, there are strong indications that Azerbaijan played a decisive role in denying foreigners, including journalists and human rights ombudspeople, access to Nagorno-Karabakh as early as December 2021. A year later, freedom of movement was dramatically restricted even further, as the Azerbaijani government supported – if not directly facilitated – protests by its citizens that blocked the corridor. The protests were eventually replaced by the creation of the formal border checkpoint, followed by the installation of a concrete barrier, ultimately reaching a state of complete prohibition of all movement of people, goods, services and humanitarian aid, including ICRC medical transport vehicles. In a recent report explaining the crisis on the Lachin Corridor, International Crisis Group wrote:

Baku appears to view the checkpoint as a way of asserting control of territory that legally belongs to Azerbaijan but remains out of its hands under the armistice terms, and which Baku now refers to as the ‘former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast.’ Indeed, a mid-level Azerbaijani official characterised the move to Crisis Group as a 'reclamation of sovereignty' (emphasis added by University Network). Another Azerbaijani official told Crisis Group that Baku will use the new checkpoint to 'observe, control and influence' Nagorno-Karabakh (emphasis added by University Network). 60

The consequences of the blockade, which commenced on December 12, 2022, have been profound, beginning with a 198-fold reduction in human mobility through the Lachin Corridor.61 Civilian travel through the Lachin checkpoint only take place as part of an ICRC transport, and after passing an onerous multi-party approval process described later in this section. Between December 2022 and March 2023, the ICRC had conducted 35 medical evacuations for 205 patients in need of medical care, and had facilitated the transfer of 422 people for family reunifications.62

As a result of the virtual prohibition on travel into and out of Nagorno-Karabakh, its residents experienced persistent and wide-ranging violations of economic and social rights, culminating in grave threats to and violations of the right to life. A representative of the ICRC described to the University Network how, as result of Azerbaijan's blockade of the Lachin Corridor, violations of the right to food and an adequate standard of living would culminate to undermine the right to health of the residents of Nagorno-Karabakh. The humanitarian support provided by the ICRC was not sufficient to meet the needs of the entire population impacted by the blockade. In March 2023, an ICRC representative told UNHR,

"We are trying to rebuild contingency stocks. We realize there are certain pressing needs that we are partially somehow able to mitigate, but we can not claim that we are covering them in full. These restrictions on basic goods and services necessary for an adequate standard of living threaten to create medical emergencies which will need to be treated in Armenia."63

The Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh conducted systematic, in-field documentation of the human rights impacts of the blockade. They published their findings periodically in comprehensive reports alerting the international community to the perilous effects on the health of vulnerable groups, particularly infants, women and young girls, persons with disabilities, and the elderly. UNHR was later able to collect firsthand testimonies of life under the blockade in late September 2023, immediately after the majority of ethnic Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh had arrived in Goris, Armenia.

The health impacts of the dramatic reduction in food and medicine supplies were severe. In June 2023, the Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh had warned that lack of sustenance and medication had resulted in an increase in morbidity, including a 61 percent rise in coronary heart disease, a 38 percent increase in cerebral palsy, and a 12.2 percent surge in childbirth complications, in comparison to the same period the previous year.64 A refugee from Nagorno-Karabakh who spoke with UNHR researchers in Goris described how drastically the public health situation had deteriorated:

"The conditions were unbearable, and it kept getting worse. … If someone was in a very grave condition, I would go there to help, thinking whatever happens, happens. I would transfer people to the hospital, but many people died in Stepanakert. Pregnant women suffered from malnutrition, leading to miscarriages."65

According to a statement from the Nagorno-Karabakh Ministry of Health, the eight-month blockade exacerbated stress and hunger levels, resulting in anemia in over 90 percent of pregnant women and a tripling of early-stage miscarriage rates.66

For the hundreds of newborns born under the blockade, the periodic acute shortages of infant formula were a source of significant stress. One family said in an interview with the Human Right Defender of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh that the stress of the formula shortage was compounded by finding themselves on the Armenian side of the blockade for six months while their newborn remained in Nagorno-Karabakh: Twenty-three-year-old Mariam from Stepanakert told the Human Rights Defender,

I couldn’t even imagine in my worst nightmare that I will be separated from my baby for such a long time. Every time I call my mother and she shows me my son, I can’t hold my tears and I start to cry my heart out… My mother has a chronic disease, she is not able to go and queue for food for hours, nor she is able to go and search for the necessary infant formula for Sevak all over Stepanakert. I will not forgive myself if something bad happens to my baby.67

For 9,000 individuals with disabilities, being cut off from rehabilitation centers (located in Armenia) led to deterioration of their physical and mental health. The elderly were also disproportionately affected by the loss of access to medicine and treatment for chronic illnesses and access to nutritious food. Among the Human Rights Defender's particularly distressing findings was the deep mental health harm caused by stress and isolation on the elderly, for whom, compounded by their physical ailments,

“every new day of the blockade [was] a life-and-death struggle.”68

5. Disruption of Energy Infrastructure

Throughout 2022, Azerbaijan's adopted a series of measures that led to increasingly more critical disruption of Nagorno-Karabakh's energy infrastructure. It began in March 2022, when the flow of gas to Nagorno-Karabakh came to a sudden halt, apparently resulting from an explosion in a portion of the pipeline passing through Shushi in Azerbaijani-controlled territory.69 Then, in September 2022, Azerbaijan acquired control of electricity cables traversing the Lachin Corridor.70 On January 9, 2023, one month into what became the 10-month blockade of the Lachin Corridor, local power-grid operator ArtsakhEnergo reported that the only cable transporting electric power from Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh was damaged, again in Azerbaijani-controlled territory.71

A Severed Gas Pipeline

On March 8, 2022, Nagorno-Karabakh’s main gas pipeline from Armenia was damaged, leaving residents without hot water or heating. The initial incident and Azerbaijani officials’ subsequent refusal to receive a repair team are indicative of Azerbaijan’s intentional obstruction of the proper functioning of basic utilities. The case also demonstrates Azerbaijan’s abuse of its disproportionate control over infrastructure affecting daily life in Nagorno-Karabakh to exert material and psychological pressure on residents.

The head of the Office of the Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh Gegham Stepanyan released this statement in response to the incident:

As a result of the investigations carried out by the staff of the Artsakh Human Rights Defender and discussions with the law enforcement bodies, it turned out that the gas pipeline was damaged in the area under the control of the Azerbaijani Armed Forces. The specialists of 'Artsakhgaz' CJSC and representatives of law enforcement bodies of Artsakh cannot clearly state whether the accident took place due to technical reasons or as a result of the actions of the Azerbaijani side, the reason is that the Azerbaijani side obstructs the access of representatives of law enforcement bodies and specialists of gas supply company to the place of accident.72

The refusal to allow officials and technical experts to explore the damaged area and Azerbaijan's failure to restore the pipeline until Russia got involved on March 19 – 11 days after the initial damage was reported – lends support to the claim that the damage to the pipeline was intentional.

The controversy did not end there. Two days later, the flow of gas stopped again. Officials in Nagorno-Karabakh said, “We have sufficient ground to state that during the repair work of the gas pipeline that exploded on 8 March, the Azerbaijani side installed a valve through which it stopped the gas supply hours ago.”73 The International Crisis Group, an independent organization reporting on threats of war worldwide, independently reported on the incidents:

De facto authorities allege that Azerbaijanis engineered an explosion to stop supplies during extremely cold weather. Azerbaijani authorities rejected Russian peacekeeper requests to provide access for repair crews from Armenian-controlled territory. Although the Russians patched the pipeline themselves, no gas flowed for eleven days – and then returned for only two days before another break in service until 29 March.74

The University Network witnessed the evidence of the gas shortage firsthand. During our drive to Nagorno-Karabakh on March 24, 2022, we stopped at a gas station in Goris, about 35 kilometers (nearly 22 miles) from the entry point to the Lachin Corridor. We saw a line of individuals carrying small gas canisters, filling them at the gas station to transport them back to Nagorno-Karabakh. (Again, this was eight months before the blockade of the Lachin Corridor began).

Azerbaijani media coverage of the damaged pipeline is sparse. The Azerbaijani Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a statement denying the allegations of intentional harm: “As for the technical problems in the gas pipelines in the region due to severe weather conditions for several days, Armenia intends to use the situation as a tool for political manipulation.”75

Though Russian forces and various state-associated organizations purportedly conducted investigations into the event, severe disruptions in the gas supply to Nagorno-Karabakh continued through the mass forced exodus in September 2023. According to the Nagorno-Karabakh Human Rights Defender,

On December 13-16, 2022, at around 6:00 pm, in severe winter conditions, the Azerbaijani authorities cut off the supply of natural gas from Armenia to Artsakh, depriving the Artsakh civilian population of the basic necessities necessary for safeguarding its livelihood. The gas supply to the entire territory of Artsakh was cut off again by Azerbaijan on January 18, 2023, at around 01:00 pm, leaving the majority of Artsakh’s households still without access to heating and hot water in the dead of winter.76

In conjunction with the blockade of the Lachin Corridor that began in December 2022, the severing of the pipeline was an energy crisis in the making.

The disruption in the flow of power to Nagorno-Karabakh caused widespread harm on numerous aspects of daily life: regular six-hour rolling blackouts as well as emergency blackouts; shortages of hot water for cooking, cleaning and personal hygiene; increasing reliance on wooden stoves for heating causing respiratory health impacts; periodic internet and cellphone network blackouts increasing isolation and insecurity; and periodic school closures leading to mental health and behavioral impacts on children and families.77

A refugee from Nagorno-Karabakh who spoke with UNHR in Goris described how these impacts manifested in his daily life:

"There was no water, and electricity was only available for four hours a day. The electrical circuit couldn't handle the voltage from the heaters in the winter, so only the strong ones could take cold showers. Others could only wash their children once a month when they could heat water on a stove. The conditions were unbearable, and it kept getting worse."78

Together, the events described above drastically increased the enclave's reliance on scarce internal water resources to generate hydroelectric power. As early as January 2023, the Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh warned, “[L]ocal production of electricity is carried out mostly through the Sarsang Hydro-Power Plant, where water in the Sarsang reservoir is used in large volumes to generate electricity. Continuing use of the reservoir in these volumes will deplete capacity quickly, and longer rolling blackouts will need to be imposed.”79

Sarsang Reservoir

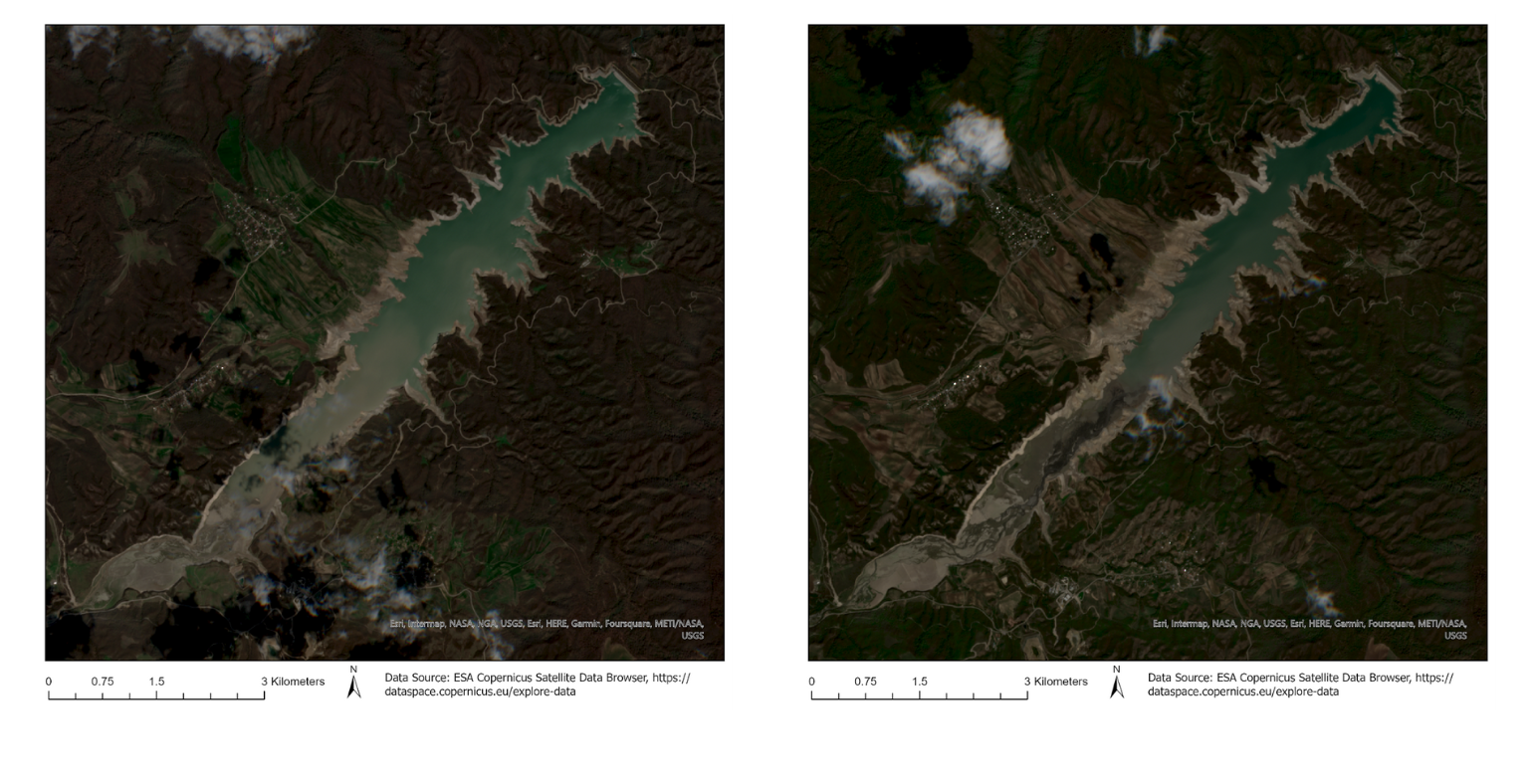

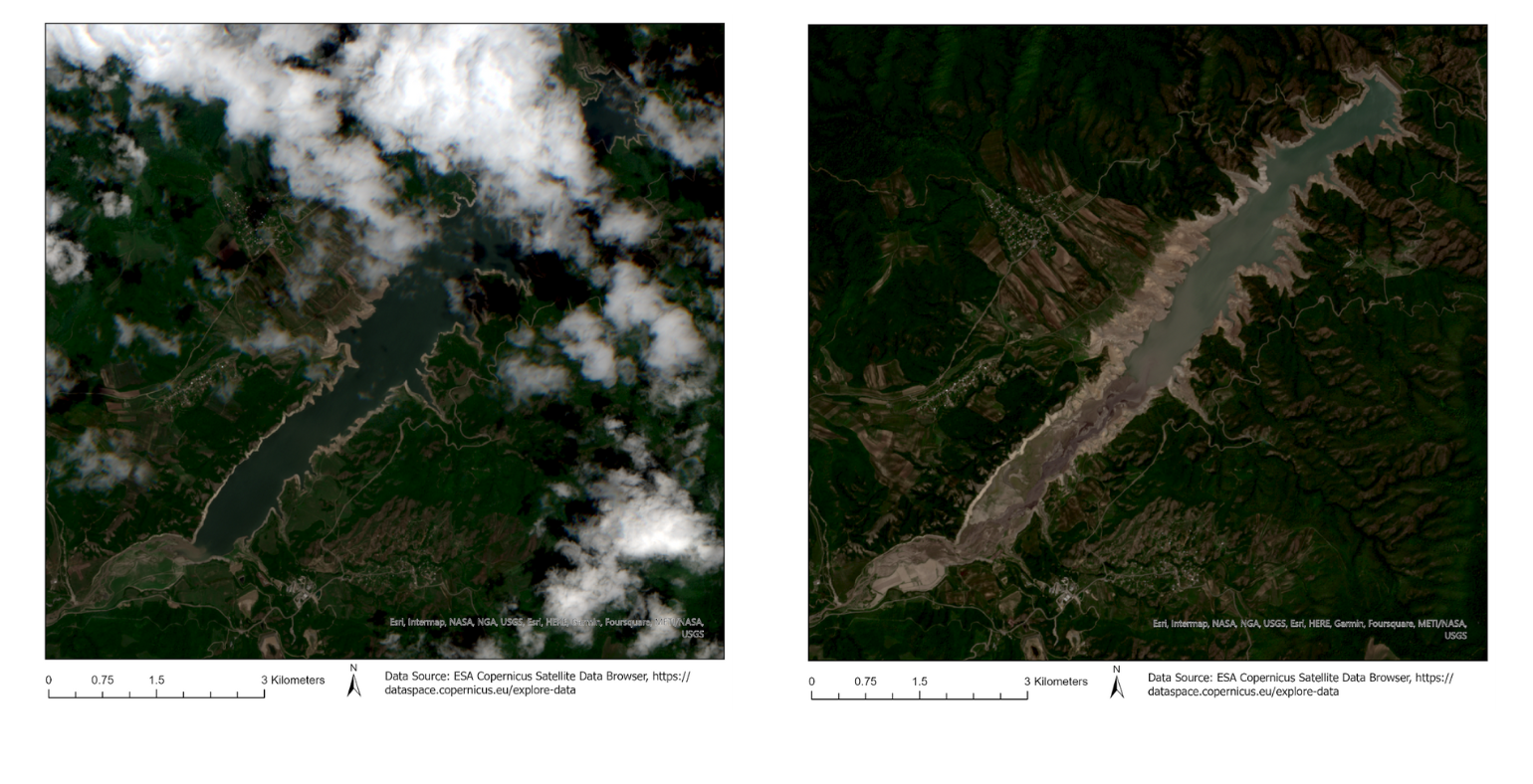

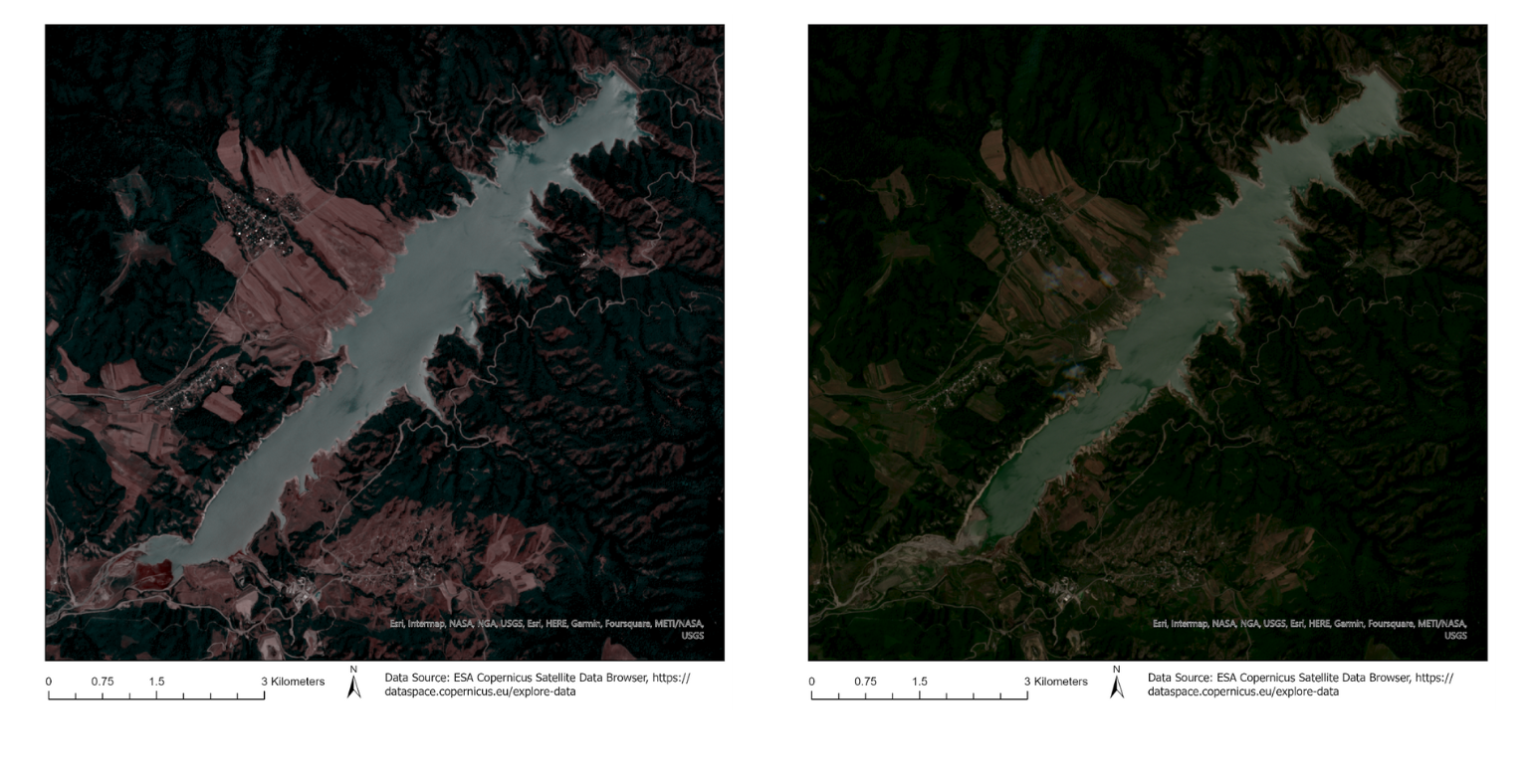

Independent analysis of satellite imagery of Sarsang Reservoir was conducted for this report by a team at the Department of Earth & Environmental Science at Wesleyan University.

During 2023, it was evident from satellite data that there was a noticeable decline in the water level of the Sarsang Reservoir. This decline was especially precipitous in the reservoir’s southwestern half, which drained altogether for several weeks, though the reservoir in its entirety was affected. The reservoir was most strongly affected during the late spring and summer of 2023, though the stress on its water levels was severe enough that effects have continued in recent months. The changes during the aforementioned periods were significant and visible to the naked eye via publicly-available satellite imagery (Sentinel-2).

In April of 2019, the reservoir level was lower than in February 2019, most likely due to the change in seasons. In April 2023, however, the drainage was much more significant, especially in the southwestern portion of the reservoir. Additionally, the water level of the upper west part of the shoreline was significantly lower than in the same month in 2019.

The Sarsang reservoir’s water levels were significantly different in May 2023 when compared visually to May 2019. The impact to reservoir water levels was drastic across the reservoir as a whole, with almost the entire southwestern half of the reservoir fully drained.

While in July of 2023 water levels had increased compared to earlier months of the same year, they were still notably lower than in July of 2019. Once again, the southern tip and the western shoreline were drained much more than in a typical year.

6. Endangerment of Food Security

Limited access to food became an existential threat to Nagorno-Karabakh residents months before the September 2023 assault. Azerbaijan’s blockade essentially halted the import of food products and fuel (needed to transport food internally), rendering the population of Nagorno-Karabakh far more reliant on internal and local food production than it had been before the blockade. In parallel, Azerbaijani forces’ attacks on farming and agricultural lands (see “Attacks on Sources of Livelihood” above), combined with a shortage of fertilizers and pesticides resulting from the blockade, caused a reduction in local food production, putting the population of Nagorno-Karabakh on a path to starvation.80

The ICRC described fruit, vegetables, and bread as “increasingly scarce and costly” and said many important food items, including dairy, cereal, and chicken, were no longer available in Nagorno-Karabakh as of late July.81 In its February assessment of the blockade, the International Court of Justice acknowledged evidence of food shortages and found that restricting Nagorno-Karabakh’s access to humanitarian supplies, including food, “may have a serious detrimental impact on the health and lives of individuals.”82

Many of the people who spoke with UNHR researchers after fleeing to Armenia in September 2023 shared their personal stories of living on the brink of starvation during the blockade. A middle-aged woman from Martuni told us,

We were thirsty, tired, going to sleep hungry. We have been living, starving, and malnourished. After June 15, life was much worse. We had rations before June 15, but after June 15 we used pig fat to make coffee. There was no flour. We were already at death’s door. Most of our food was going to keep the soldiers sustained. People were selling their jewelry and personal things to buy food.83

“We spent the last nine months in hunger.”

“We spent the last nine months in hunger. People would look for bran. . . . They would grind it and mix it with some flour and eat. That’s what one would feed to pigs normally. People would cook crepes on a bonfire made from that black substance and feed it to their children so that they don’t remain hungry. People looked for any sort of food, exchanged and shared whatever they could find in their gardens. Everything was very expensive – tomatoes cost 3000 drams (about $8). To get a loaf of bread, we had to walk one and a half kilometers, register in the queue and get a number. There were even people who got killed in the queues. One child died in that way while two women were fighting for their place in the bread queue, in Stepanakert. After one round of bread queuing, we would go home and return to the queues in three hours for a new attempt. I would do three attempts and get one loaf of bread, best case; often, we’d go home empty-handed. One person would get a loaf of bread and share it between ten people. There was no flour. None of the neighbors had flour to share with others. When we were told that the authorities were distributing salt or flour, by the time we would make it to the distribution point, the food would already be gone.84

- Middle-aged mother of two from the Askeran region. Interview with UNHR, Goris. September 29, 2023.

In August, the former chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court issued a report asserting that the blockade of food and other essential supplies should be considered “genocide by starvation.”85 Following increasing international pressure on Azerbaijan to lift the blockade, the Azerbaijani government announced that it would facilitate passage of humanitarian aid through the Aghdam district of Azerbaijan into Nagorno-Karabakh, and would open the Lachin Corridor for humanitarian aid 24 hours later. On September 12, 2023, a single Russian ICRC vehicle traversed this road and entered Nagorno-Karabakh.

The Aghdam road deal was dangerous. Fully within undisputed sovereign Azerbaijani territory, this route and entry point into the portion of Nagorno-Karabakh populated by ethnic Armenians is impermeable to international scrutiny. However, after nine months under siege, the population of Nagorno-Karabakh and their de facto authorities were cornered and desperate. Humanitarian aid, no matter which road brought it, offered temporary relief. But even partial reliance on the Aghdam road foreshadowed not only Nagorno-Karabakh's complete dependency on Azerbaijan-approved aid, but, more profoundly, the consolidation of Azerbaijan's genocidal project of subjugating and ultimately emptying Nagorno-Karabakh of ethnic Armenians. That project reached completion exactly one week after the lone aid truck entered Nagorno-Karabakh through the Aghdam road.

Armenian organizations analyzed and spoke out about these dangers, but the international community did not listen. Instead, high-level officials from the United States and Europe encouraged the Aghdam road deal. Samantha Power, Administrator of the United States Agency for International Development, expressed, “It is essential that the Aghdam and Lachin routes be reopened immediately;”86 the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs said, “The Lachin Corridor must be reopened now. Other roads, such as Aghdam, can be part of the solution, but not an alternative.”87 US Acting Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs Yuri Kim “welcomed the news that one shipment carrying approximately 20 tons of humanitarian supplies passed through the Aghdam route into Nagorno-Karabakh.”88

Ultimately, the collapse of food security in Nagorno-Karabakh, followed by Azerbaijan's imposition of “reintegration” (see Final Chapter) of the ethnic Armenian population into the Azerbaijani state, was one of the decisive factors contributing to making life in Nagorno-Karabakh intolerable for its ethnic Armenian population.

Notably, the threat to food security has spread to border communities in Armenia. For example, there have been instances in which physical attacks have also destroyed existing food stores, exacerbating the need for new harvests and imports. Melik, a resident of the border village of Sotk told UNHR, “Eight meters from my house a missile fell, but there are more severe cases than mine. The roof, door, windows and yard were all damaged. Whatever we had harvested, we collected during this period, it was all destroyed.”89

IV. Conclusion

In the wartime and postwar period, Azerbaijani forces used a range of abusive tactics resulting in the forced displacement of ethnic Armenians. Azerbaijan deployed these tactics incrementally, steadily building toward total control of land, movement, and resources within, into, and out of Nagorno-Karabakh. These tactics included: physical attacks; intimidation through threat of further attacks, surveillance and arbitrary detention of Armenian civilians or troops in Nagorno-Karabakh, in sovereign Armenia, and at border crossings; complete control over who and what was allowed to enter and exit Nagorno-Karabakh, including humanitarian aid, through siege and blockade; selective and arbitrary cessation or blockage of essential services (gas, electricity); deliberate attacks on sources of livelihood – namely agricultural lands and livestock, as well as tourism assets; and endangerment of food security. Azerbaijan’s violations of international laws and norms prohibiting forced displacement are related to its myriad other violations of human rights enumerated in this report. Each mutually contributed to and were exacerbated by the six mechanisms of forced displacement, creating an environment that was ultimately unlivable for the Armenian residents of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Endnotes

1. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Handbook for the Protection of Internally Displaced Persons: Part V: Protection Risks: Prevention, Mitigation and Response. Action Sheet 1 - Forced and Unlawful Displacement, 2007, The United Nations, available at: https://www.unhcr.org/media/handbook-protection-internally-displaced-persons-part-v-protection-risks-prevention-4

2. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, December 2010, The United Nations, available at: https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/convention-and-protocol-relating-status-refugees

3. UN Commission on Human Rights, Addendum: Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, 11 February 1998, E/CN.4/1998/53/Add.2, available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G98/104/93/PDF/G9810493.pdf?OpenElement

4. International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (Fourth Geneva Convention), 12 August 1949, 75 UNTS 287, available at: https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/atrocity-crimes/Doc.33_GC-IV-EN.pdf

5. UN General Assembly, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, art. 13, 10 December 1948, United Nations, available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/human-rights/universal-declaration/translations/english [hereinafter “UDHR”]

6. UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, art. 12, 16 December 1966, United Nations, available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights [hereinafter ICCPR].

7. UN General Assembly, International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, art. 5, 21 December 1965, United Nations, available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-convention-elimination-all-forms-racial [hereinafter ICERD]

8. UN General Assembly, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, art. 15. December 1979, United Nations, available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-elimination-all-forms-discrimination-against-women [hereinafter “CEDAW”]

9. UN General Assembly, Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, art. 7, 17 July 1998, International Criminal Court, available at: https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/RS-Eng.pdf [hereinafter “Rome Statute”]

10. Ibid, art. 8.

11. International Criminal Court (ICC), Elements of Crimes, Footnote 12, 2013, The Hague, available at: https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/Publications/Elements-of-Crimes.pdf

12. UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, 22 July 1998, ADM 1.1,PRL 12.1, PR00/98/109, available at: https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/guiding-principles-internal-displacement

13. Ibid, Principle 6.

14. UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, Principle 9. 1998, ADM 1.1,PRL 12.1, PR00/98/109, available at: https://www.unhcr.org/us/media/guiding-principles-internal-displacement

15. Susana Petrosyan, interview with UNHR, Stepanakert, March 25, 2022,

16. Name has been changed for security reasons.

17. Melik, interview with UNHR, Sotk, March 14, 2023.

18. Name has been changed for security reasons.

19. Samvel, interview with UNHR, Sotk, March 14, 2023.

20. Name has been changed for security reasons.

21. David, Interview with UNHR, Sotk, March 14, 2023.

22. David, interview with UNHR, Sotk.

23. Name has been changed for security reasons.

24. Artur, interview with UNHR, Sotk, March 14, 2023.

25. Melik, UNHR interview, Sotk.

26. Samvel, interview with UNHR, Sotk.

27. Zara Amatuni, International Committee of the Red Cross, UNHR Interview in Yerevan, March 21, 2023. [Henceforth: ICRC interview, March 2023]

28. ICRC interview, March 2023

29. Mother of two boys, interview with UNHR, Jermuk, March 16, 2023. Names are not used for security reasons.

30. Mother of two boys, interview.

31. Mother #2, interview with UNHR, Jermuk, March 16, 2023. Names are not used for security reasons.

32. David, interview.

33. Kut Village Head, interview with UNHR in Kut, March 14, 2023.

34. Vahram, interview with UNHR in Goris, March 17, 2023.

35. Susana Petrosyan, interview with UNHR in Stepanakert, March 25, 2022.

36. Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Artsakh. 2023. “Interim Report on Violations of the Rights of Artsakh People by Azerbaijan in February - March.” artsakhombuds.am. https://artsakhombuds.am/en/document/910.

37. Caliber.Az. 2023. “30th anniversary of the Khojaly genocide. Azan sounds in Pirlar and Khanabad.” Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=5129718323745410&ref=sharing.

38. “Azerbaijanis have been 'calling' the people of Khramort to leave the village with loudspeakers for 3 days.” 2022. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JyFmLHsKkUs. Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Artsakh. 2023. “Interim Report on Violations of the Rights of Artsakh People by Azerbaijan in February - March.” artsakhombuds.am. https://artsakhombuds.am/en/document/910.

39. Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Artsakh. “Interim Report on Violations of the Rights of Artsakh People by Azerbaijan in Februrary - March,” 17.

40. Tigran, interview with UNHR in Kut, March 14, 2023. Name has been changed for security reasons.

41. Ministry of Defense of the Republic of Armenia. 2023. “Release.” Ministry of Defense of the Republic of Armenia. https://mil.am/hy/news/10146.; Artsakh Republic National Security Service. 2021. “The National Security Service of the Republic of Artsakh is taking measures to return the citizen of Artsakh who came under the control of the Azerbaijani armed forces as a result of getting lost.” Artsakh Republic National Security Service. https://www.nssartsakh.am/hy/news/arcaxi-hanrapetutyan-azgayin-anvtangutyan-carayutyun-mijocner-e-jernarkum-molorvelu-ardyunkum-adrbejani-zinvac-uzeri-verahskogutyan-tak-haytnvac-arcaxcun-veradarjnelu-uggutyamb.

42. Badalyan, Susan. 2021. “A tractor driver from the village of Tegh 'violated' the border by 10 meters and caused 5-hour trilateral negotiations.” Радио Азатутюн. https://rus.azatutyun.am/a/31367199.html.

43. Armen Press. 2021. “Artsakh's citizen who was lost and entered the territory under Azerbaijani control has been returned.” https://armenpress.am/eng/news/1058864.

44. Stepanyan, Gegham. July 26, 2021. https://www.facebook.com/gegham.stepanian/posts/3904332026362849.

45. Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Artsakh. 2023. “Report on the Violations of Individual and Collective Human Rights as a Result of Azerbaijan's Blockade of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) (100 Days).” Artsakh Ombudsman. https://artsakhombuds.am/en/document/1028, 37.

46. Ibid.

47. Ibid, 21.

48. Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Artsakh. “Interim Report on Violations of the Rights of Artsakh People by Azerbaijan in February - March,” 17.

49. Ibid.

50. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2018. “Armenia at a glance | FAO in Armenia | Продовольственная и сельскохозяйственная организация Объединенных Наций.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/armenia/fao-in-armenia/armenia-at-a-glance/ru/.

51. Hayk, interview with UNHR, Kut, March 14, 2023.

52. Kut Village Head, interview.

53. Hayk, interview.

54. Kut Village Head, interview.

55. Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Armenia. 2021. “270 hectares of pastures and 150 hectares of grasslands have been burnt in 4 villages as a result of the fires set by the Azerbaijani servicemen.” ombuds.am. https://ombuds.am/en_us/site/VideoGalleryView/588.

56. Armenia News. 2021. “Ombudsman: Azerbaijanis burned section of road from Norabak village to Azat.” NEWS.am. https://news.am/eng/news/661292.html.

57. Zoya, interview with UNHR, Kornidzor, July 2023.

58. Zoya, interview.

59. Cable Car Operator, UNHR Interview in Jermuk, March 16, 2023.

60. “New Troubles in Nagorno-Karabakh: Understanding the Lachin Corridor Crisis,” May 22, 2023, https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/caucasus/nagorno-karabakh-conflict/new-troubles-nagorno-karabakh-understanding-lachin-corridor-crisis.

61. Human Rights Ombudsman of the Republic of Artsakh. “Report on the Violations of Individual and Collective Human Rights as a Result of Azerbaijan's Blockade of Artsakh,” 5.

62. ICRC interview, March 2023

63. Ibid.

64. Human Rights Ombudsman Of the Republic Of Artsakh. “Report on the Violations of Individual and Collective Human Rights as a Result of Azerbaijan's Blockade of Artsakh,” 12.

65. P-0026, UNHR Interview in Goris, September 30, 2023.

66. Martirosyan, Lucy, and Siranush Sargsyan. 2023. “Nagorno-Karabakh blockade: Mothers tell of life in a humanitarian crisis.” Open Democracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/mothers-nagorno-karabakh-artsakh-armenia-azerbaijan-children/; Dovich, Mark. 2023. “Miscarriages surge in Karabakh amid widespread food shortages.” CivilNet. https://www.civilnet.am/en/news/745150/miscarriages-surge-in-karabakh-amid-widespread-food-shortages/.

67. Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Artsakh.“Report on the Violations of Individual and Collective Human Rights as a Result of Azerbaijan's Blockade of Artsakh.” Quoting from interview with Mariam, 9.

68. Ibid, 33.

69. Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Artsakh. “Interim Report on Violations of the Rights of Artsakh People by Azerbaijan in February - March, ” 11-12.

70. Avetisyan, Ani. 2023. “Weaponizing Energy: Nagorno-Karabakh’s Energy Supplies Under Siege.” EVN Report. https://evnreport.com/spotlight-karabakh/weaponizing-energy-nagorno-karabakhs-energy-supplies-under-siege/.

71. Khulian, Artak. 2023. “Azerbaijan Accused Of Blocking Power Supply To Karabakh.” Ազատություն [Azatutyun]. https://www.azatutyun.am/a/32219156.html.

72. Human Rights Defender Of the Republic Of Artsakh. 2023. “Due to the damage to the main gas pipeline coming from the Republic of Armenia to Artsakh, the whole territory of Artsakh is deprived of gas supply.” Artsakh Ombudsman. https://artsakhombuds.am/en/news/635.

73. Armenia News. 2023. “Due to Direct Interference of Azerbaijani Side, Gas Supply to Artsakh Is Stopped Again.” news.am. https://news.am/eng/news/692589.html.

74. International Crisis Group. 2022. “Nagorno-Karabakh: Seeking a Path to Peace in the Ukraine War's Shadow.” Crisis Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/caucasus/nagorno-karabakh-conflict/nagorno-karabakh-seeking-path-peace-ukraine.

75. Əli Mahmudlu-Frontend Web Developer- Edumedia Azerbaijan, “No:139/22, Statement by the Press Service Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan on the groundless allegation of the Armenian Foreign Ministry regarding the situation in the region,” accessed March 20, 2023, https://www.mfa.gov.az/en/news/xin.gov.az.

76. Human Rights Defender Of the Republic Of Artsakh. 2023. “Interim Report on the Violations of Human Rights of Artsakh People as a Result of the Deliberate Disruption of Critical Infrastructure in the Midst of the Blockade of Artsakh by Azerbaijan Since December 12, 2022.” Artsakh Ombudsman. https://artsakhombuds.am/en/document/987.

77. Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Artsakh. “Report on the Violations of Individual and Collective Human Rights as a Result of Azerbaijan’s Blockade of Artsakh.”

78. P-0026, UNHR Interview in Goris.

79. Human Rights Ombudsman Of The Republic Of Artsakh. 2023. “Interim Report on the Violations of Human Rights of Artsakh People as a Result of the Deliberate Disruption of Critical Infrastructure in the Midst of the Blockade of Artsakh by Azerbaijan Since December 12, 2022.”

80. Khulian, Artak. 2023. “Azerbaijani Troops Accused Of Shooting At Karabakh Farmers.” Ազատություն Ռադիոկայան [Azatutyun Radio]. https://www.azatutyun.am/a/32333072.html.

81. Sator, Fatima. 2023. “Azerbaijan/Armenia: Sides must reach “humanitarian consensus” to ease suffering.” International Committee of the Red Cross. https://www.icrc.org/en/document/azerbaijan-armenia-sides-must-reach-humanitarian-consensus-to-ease-suffering.

82. International Court of Justice. 2023. “Summary of the Order of 22 February 2023”. International Court of Justice. https://www.icj-cij.org/node/202558.

83. P0035, UNHR Interview in Artashat, October 15, 2023.

84. P0012, UNHR Interview in Goris, September 29, 2023.

85. Ocampo, Luis M. 2023. “Former International Criminal Court prosecutor, Luis Moreno Ocampo, issued report stating the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh is “Genocide.”” Center for Truth and Justice. https://www.cftjustice.org/former-international-criminal-court-prosecutor-luis-moreno-ocampo-issued-report-stating-the-blockade-of-nagorno-karabakh-is-genocide/.

86. Samantha Power [@PowerUSAID] “The Humanitarian Situation in Nagorno-Karabakh Is Rapidly Deteriorating. It’s Essential That the Lachin and Aghdam Routes Be Reopened Immediately so Lifesaving Assistance Can Reach the People of NK.,” Tweet, Twitter, September 10, 2023, https://twitter.com/PowerUSAID/status/1700917236771291627.

87. Josep Borrell Fontelles [@JosepBorrellF], “In a Call with Foreign Minister @Bayramov_Jeyhun, I Reiterated My Concerns Regarding the Humanitarian Situation Facing Karabakh Armenians. The Lachin Corridor Must Be Re-Opened Now. Other Roads, Such as Aghdam, Can Be Opened as Part of the Solution, but Not an Alternative.,” Tweet, Twitter, September 9, 2023, https://twitter.com/JosepBorrellF/status/1700548396375847096.

88. “Statement of Yuri Kim, Acting Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs Before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee,” September 14, 2023, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/6667fb89-a975-4fab-d8b8-e8875312e37e/091423_Kim_Testimony.pdf.

89. Melik, interview.